By MALUM NALU

Exactly two years ago, in October 2008, I travelled around Bulolo with local MP Sam Basil, checking out various projects in his electorate.

|

| Upper Watut warriors of Bulolo |

At Manianda in the Upper Watut local level government, along the road to Menyamya, Wau-Bulolo mayor and long-time Sepik settler, Jack Nawie, sent a blunt warning to criminal elements that there must be “zero tolerance” of crime in these two towns.

|

| Happier days…Wau-Bulolo mayor Jack Nawie (left) with Bulolo MP Sam Basil in Upper Watut… ‘zero tolerance’ of crime in Wau and Bulolo |

In retrospect, looking back at what Nawie said that day, I can only say that he has must have had a crystal ball in hand.

I say this in light of the recent ethnic clashes in Bulolo between the local people and Sepik settlers and, to a lesser extent, that between the Watut and Biangai people last year.

Nawie said that fateful day that the two historical gold mining towns were once again experiencing a boom and mining and exploration activities and their “cowboy town” tags must be disposed of to attract more investment.

|

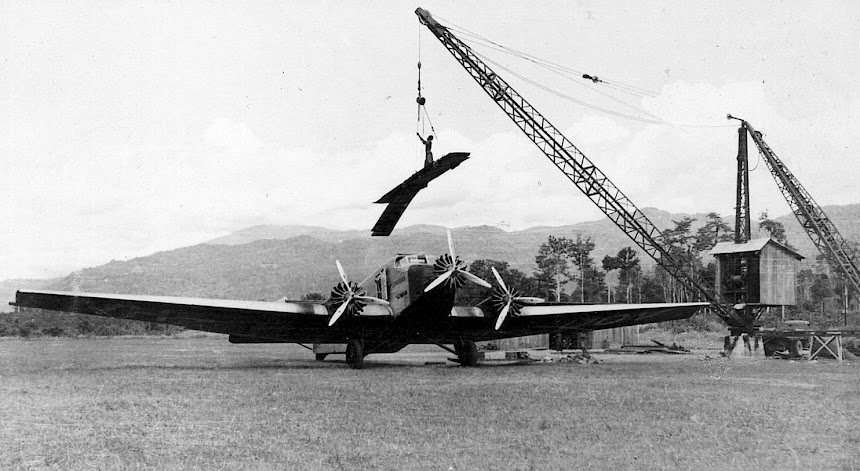

| Aerial shot of a gold dredge in Bulolo. The rivers and creeks around Bulolo and Wau abound with alluvial gold |

“As the manager of these towns, I will not tolerate these criminal activities anymore,” he said.

“There will be ‘zero tolerance’ of criminal activities.

“As manager of these towns, I want companies to come and invest here.

“We don’t want the ‘cowboy town’ image of Wau and Bulolo to come back and haunt us.

“We will work closely with all companies already here and those who want to come in as they are bringing services and we want to support them.

“I also want to raise the level of the two towns from urban level 2 to Urban Level 1 because of the current boom in mining and exploration.

“I will work closely with Bulolo MP Sam Basil and other LLG presidents to push for development in these two towns.”

Nawie is originally from East Sepik but, like many others, was born and raised in Bulolo and calls it “home”.

“This is my town and this is my place,” he said.

“My heart lies where I was born.”

Unfortunately, starting in April this year, fighting in Bulolo started to escalate with more than 5,000 villagers taking part in the raid on Sepik settlers.

Local villagers have been walking the length and breadth of Bulolo armed with guns, knives and bows and arrows in open defiance of police.

Surrounding Sepik settlements including Cement Bridge, Maramba, White House, Biwat, Tambanum, Kapriman, Aitape and Sangriwa have been razed.

The situation has affected the operations of all major companies in Bulolo such as PNG Forest Products (PNGFP), Bank South Pacific, post office, schools, health centre and University of Technology Bulolo campus and retail outlets – forcing all to close.

More than 2,000 settlers have been using the PNGFP camp site as a care centre, having lost everything except the clothes on their backs, and have sought police protection as locals try to penetrate the area.

Amidst all this gloom and doom, it must not be forgotten that the Sepiks of Bulolo are no ordinary settlers.

Their great grandfathers, grandfathers and fathers were pioneers of Bulolo, coming in with the first white men to Bulolo Valley.

They were brought in by Bulolo Gold Dredging, forerunner to the current PNGFP, according to Michael Waterhouse’s brand new book on the Wau-Bulolo goldfields titled Not A Poor Man’s Field.

“Nor did BGD neglect its indentured labourers,” Waterhouse writes.

“Most came from villages in the Sepik district and were recruited for two or three years, usually as general labourers for which they were paid six shillings per month.

“They were used to unload planes, to clear jungle ahead of the dredges and as assistants to the many different tradesmen at Bulolo, telephone switchboard operators, messengers, waiters, labourers, personal servants, cooks and houseboys.

“BGD realised at the outset that, allowing for normal turnover, it would need many labourers, and that it would be more successful in attracting them if they returned to their villages happy that BGD had treated them well.

“The huts were located within compounds, which had electricity, running water and showers and a septic tank sewerage system.

“Close by were gardens containing kaukau, taro, corn, paw paws and bananas.

“There was also a trade store, where goods could be purchased and which distributed food rations and clothing.

“BGD paid particular attention to the health of its labourers.

“They invariably arrived from their villages in a fairly-debilitated condition.

“Within a short time, however, good food and exercise filled out their physique.

“They had access to a high standard of medical services, Bulolo having the best-equipped hospital in the Territory.

“As a result, their mortality rate was considerably less than elsewhere on the goldfields.

“It is hardly surprising that there was never a shortage of villagers from the Sepik and elsewhere lining up to work at Bulolo.”

Indigenous labour was pivotal to the success of the goldfield, and this was provided by a highly-organised indentured labour system.

“An indentured labour system had been developed by the Germans, and this was maintained by Australian military and then civil administration,” Waterhouse writes.

“Labourers were recruited from villages in areas previously opened up to European influence and transported, often over long distances, to where they were needed.

“They signed contracts, at first for one or two years, but in the 1930s more commonly for three, during which they were indentured to specific employers.

“Whereas villagers in New Britain and New Ireland who otherwise lacked access to the cash economy tended to work on plantations, those from the Markham Valley and elsewhere in the Morobe district naturally gravitated towards the goldfields.

“But as the growth of mining outstripped the district’s capacity to provide the labour needed, many labourers were recruited elsewhere, particularly in the Madang and Sepik districts

“In 1926, there were no Sepik labourers on the Morobe goldfields, but by the late 1930s they accounted for 30% of the total.”

The reason was summed up by researcher Richard Curtain: “The Sepik River and its numerous tributaries provided a unique opportunity for labour recruiters by making possible deep penetration into an unproductive but densely-populated interior.

“The main river is navigable for at least 1,000km for vessels up to 200 tonnes,

“The lack of alternatives cash-earning opportunities meant a readily-available workforce once initial resistance had been overcome and the relative attractiveness of work conditions on the Bulolo goldfields known in the mid-1930s.”

Gotokwa Bengo was about 18 when he went to work for BGD, leaving his village in the Keram River area in the Sepik when he heard that young men were wanted to work on the goldfields, and was taught to operate a pump, near Wau.

“In the morning, the bell would be rung at about 6am and we would get up and set off for work, in that very cold climate,” he says in Not A Poor Man’s Field.

“When I touched the water, it was just like ice.

“At about 12 noon, the bell would go again and we would come back to our quarters for lunch and then go back to work at 1pm.

“The work finished at 6pm and we returned to our quarters to meet our friends.

“Every working day was the same.

“The weekends were the most-exciting times, when we went down to see inter-tribal soccer games, or went down to Salamaua to do our shopping.”

And that ladies and gentlemen, in a nutshell, is how Sepiks settlers came about to Bulolo.